February 2nd, 2022 How I grew to hate PubSub; this one weird trick for building PubSub By Jeffrey M. Barber

I’ve mentioned, in passing, that PubSub (i.e. the publisher subscriber pattern) over-commits, so I intend to dive into what I mean by this and talk about how I think about real-time services like PubSub. Having spent over half a decade as a technical leader for a very large (soft) real-time distributed system, I think it all boils down to this toy model.

@FunctionalInterface

public static interface Subscriber {

public void deliver(String payload);

}

public static class TooSimplePubSub {

public final HashMap<String, ArrayList<Subscriber>>

subscribersByTopic = new HashMap<>();

public synchronized void subscribe(

String topic,

Subscriber subscriber) {

ArrayList<Subscriber> list = subscribersByTopic.get(topic);

if (list == null) {

list = new ArrayList<>();

subscribersByTopic.put(topic, list);

}

list.add(subscriber);

}

public synchronized void publish(

String topic,

String payload) {

ArrayList<Subscriber> list = subscribersByTopic.get(topic);

if (list != null) {

for (Subscriber subscriber : list) {

subscriber.deliver(payload);

}

}

}

}

Hopefully, the Java painfully illustrates the key logic of topical PubSub. While the above is an “ok” in-process-memory pub-sub toy model, the question of transforming it into a distributed system spawns two approaches: brokers and distributed logs.

The philosophy of the broker is to manage subscribers and reliability depends on the accurate mapping of a topic to subscribers. For example, we can take a look at the AWS Gateway for one view on this approach. With AWS Gateway, a WebSocket connection is atomized and broken down into requests to something like Lambda. The novel aspect of the WebSocket connection is the introduction of the $connect and $disconnect routes which give you the opportunity to register a connection id. That connection id can then be durably persisted and published to from any machine. AWS’s Blog can describe it better than I can. The key is that the “subscribersByTopic” is made durable via distributed system magic.

The philosophy of the distributed log is to not care about the subscribers and focus on the publishes. Reliability here means that the publishes are made durable by writing them to a log. All subscribers have to do is tail the log and filter on their topic to witness new publishes. AWS Kinesis and Kafka manifest this philosophy. For many good reasons, the Kafka view is taking over in many ways.

As an interesting aside, both models can scale infinitely with subscribers and will share common challenges when scaling publishes.

Both systems are engineering challenges to scale for a variety of great reasons, but now I can define what I mean by “over-commit”. For an active event, experience, game, or anything with N subscribers. The complexity of this model will trend towards quadratic complexity if the subscribers are also publishers (i.e people). For more nuance, using pub/sub to decouple predictable systems is a fine strategy, but expecting the same pub/sub system to work for user experiences is a journey of despair.

While the user story for whatever product may demand the essential quadratic information flow (which is most games), the networking will choke on the overhead induced by pub/sub. The traditional way of solving this is with a client/server approach where the client sends its information and the server ingests it and vends data to all clients with a compact and aggregated format. For even lower latency results, clients can leverage P2P techniques; much can be said for P2P, but P2P is out of scope for this document.

As is the case with all FUD, the question now is to turn attention to how Adama will magically solve this. After all, this is marketing copy for the Adama Platform, and at some point this content must influence you to convert to customer (or to franchise and stand Adama up within your tech-stack). The magic starts with algebra, so let’s build the above model within Adama.

@static {

// anyone can create

create(who) { return true; }

}

@connected (who) {

// let everyone connect; sure, what can go wrong

return true;

}

// we build a table of publishes with who published it

// and when they did so

record Publish {

public client who;

public long when;

public string payload;

}

table<Publish> _publishes;

// since tables are private, we expose all publishes to

// all connected people

public formula publishes =

iterate _publishes order by when asc;

// we wrap a payload inside a message

message PublishMessage {

string payload;

}

// and then open a channel to accept the publish from any

// connected client

channel publish(client who, PublishMessage message) {

_publishes <- {

who: who,

when: Time.now(),

payload: message.payload

};

// At this point, we encounter a key problem with

// maintaining a table of publishes. Namely, the table

// is potentially infinite, so we have to leverage

// some product intelligence to reduce it to a

// reasonably finite set which is important for the

// product.

// First, we age out publishes too old (sad face)

(iterate _publishes

where when < Time.now() - 60000).delete();

// Second, we hard cap the publishes biasing younger ones

(iterate _publishes

order by when desc

offset 100).delete();

}

The nature of Adama provides the mapping of topics (i.e. keys) to the above state machine, and clients can connect to an instance of the above script as a document. Adama leverages the language of “connecting” rather than subscribing. Instead of publishing, Adama has clients send messages to the document.

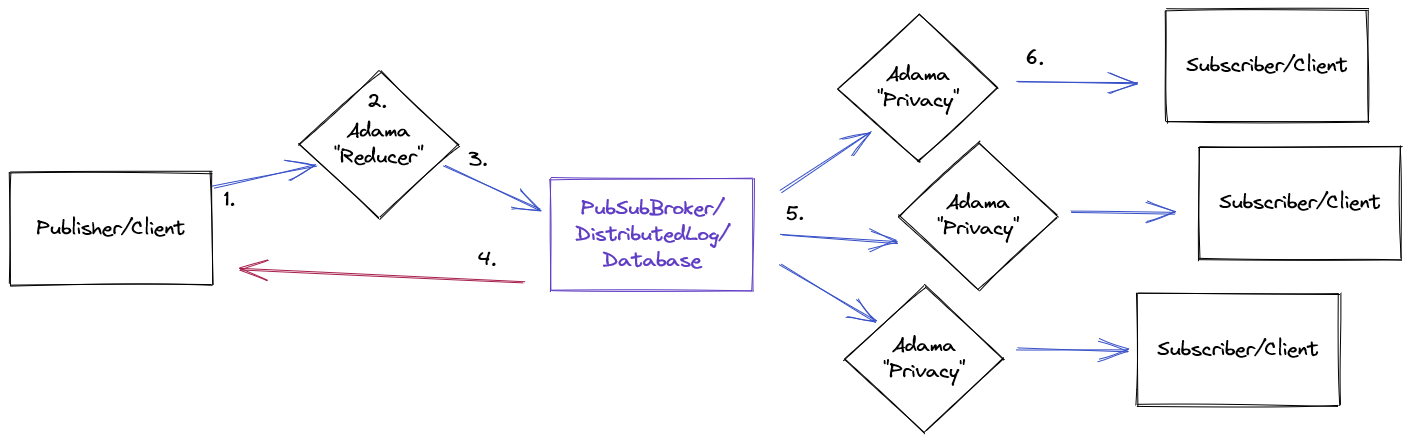

We can now study the behavior when the publishes outstrip the ability to deliver updates. This is the situation when either the publish traffic spikes or connected clients get congested and slow down. Adama will act like a reducer enforcing some product logic as to what the state should be seen. The quadratic problem is tampered down because Adama absorbs the publishes and can leverage both batching and flow control between itself and the multitude of clients. That is, Adama inserts itself in two places in an existing pub/sub system.

- The client sends a message to Adama

- Adama will ingest that message, batch it with other messages from other users, and then reduce it into a single data update

- The data update gets persisted to the database, distributed log, or whatever reliable broker is needed. Currently, Adama uses MySQL as a poor man’s log.

- The broker will durability commit the delta which Adama will happily proxy back to the client indicating that the message was accepted.

- Once the data is durable persisted, the various clients that are connected can re-compute their view

- That recomputed view is then negotiated for each client. It’s important to note that this negotiation can accommodate slow clients because the outcome is very similar to polling a document rather than ingesting an infinite command stream.

This architecture can scale horizontally with respect to people connected to documents, but the log and Adama aspect form a choke point (for a single document). However, the scaling limit of the log is significantly elevated with Adama because Adama can leverage the modern data center north-bridge’s capacity (100+ GB/second) to reduce updates which outstrips both a 10 gbit network and a 3 GB/sec NVMe.

The introduction of Adama as a reducer reduces the quadratic complexity to linear. If N publishes comes in, then Adama can crush those N publishes into one data write. That one data write is then forwarded to N subscribers. This mirrors the advantages of a traditional client-server model with a new-fangled serverless model.

Now that we have built a pub/sub system within Adama, we can see that pub/sub has a fundamental problem around message loss. It’s inevitable due to physics, and we can see it with our product rules to reduce the volume of publishes. Worse yet, the flow control between Adama and clients will coverage to a consistent end point without cross-client consistency among the intermediate points. In other words, if the product leverages the publish stream, then it may end up in wildly different places and slower clients will see less and faster clients see more. What this means is that building a product with pub/sub is not going to be fun to debug.

Given this intrinsic limit of pub/sub, many systems opt to leverage the pub/sub system as an optimistic opportunity to tell clients to re-query the database. This is perfectly sane and pretty awesome. We can implement that model with Adama as well. Here, we will let the state machine hold the most recent sequencer written to a datastore. The use case here is that you write an update to a globally replicated database which yields the writer with a sequencer. Clients can use that sequencer to understand if their regional copy is up-to-date or not.

@static {

create(who) { return true; }

}

@connected (who) {

return true;

}

public int max_db_seq = 0;

message NotifyWrite {

int db_seq;

}

channel notify(client who, NotifyWrite message) {

if (message.db_seq > max_db_seq) {

max_db_seq = message.db_seq;

}

}

Here, using Adama as a reducer acts as an algebraic optimization on the distributed log used to ship updates to all regions. If a large spike of updates happens, then the log is only burdened with the most recent sequencer at a sustainable pace. Clients will only get a stream of ever-increasing numbers, and there is no data loss.

This game of shipping a bigger and bigger number has a lot of nice properties, but it also illustrates the despair of building a pub/sub system. At least, it mirrors my despair. Suppose you go off and build a low latency distributed pub/sub system. There are all sorts of interesting tricks to make connecting publishes to subscribers exceptionally fast. It’s a fantastic game!

Well….

Most likely, the people consuming your service are simply going to take the publish (which you yielded at a breakneck speed) and then query a database. While this is great for business because making a database reactive is exceptionally hard, it’s a supreme disappointment. You set off to build a Ferrari, and the last lap of the race is taken with a geo metro.

All is not lost because you can slow down the initial laps and bias towards high throughput with batching using a F250, but the low latency Ferrari dream with hair thrashing against the wind withers away and dies a slow painful death. The business will do fine because the database is beyond important, but this is ultimately why Adama is a reactive datastore rather than a pub/sub system. A pub/sub system is too simple and requires other services like a database to do the heavy lifting for the product builders.

The worst case scenario for Adama is to leverage it like any other PubSub system. I feel the future is bright given that entire board games are being written with it point to an interesting ceiling of use-cases. So, please stay tuned for a launch of the SaaS.