January 7th, 2022 Gossip as a Failure Detector By Jeffrey M. Barber

The other day, I sat down and wrote a gossip failure detector for the Adama SaaS that I’m building. What I love about gossip is how resilient it is to failure. Currently, the gossip failure is working in unit tests and a few small scale tests. I’m running out of innovation tokens, but I feel confident implementing a gossip detector from scratch.

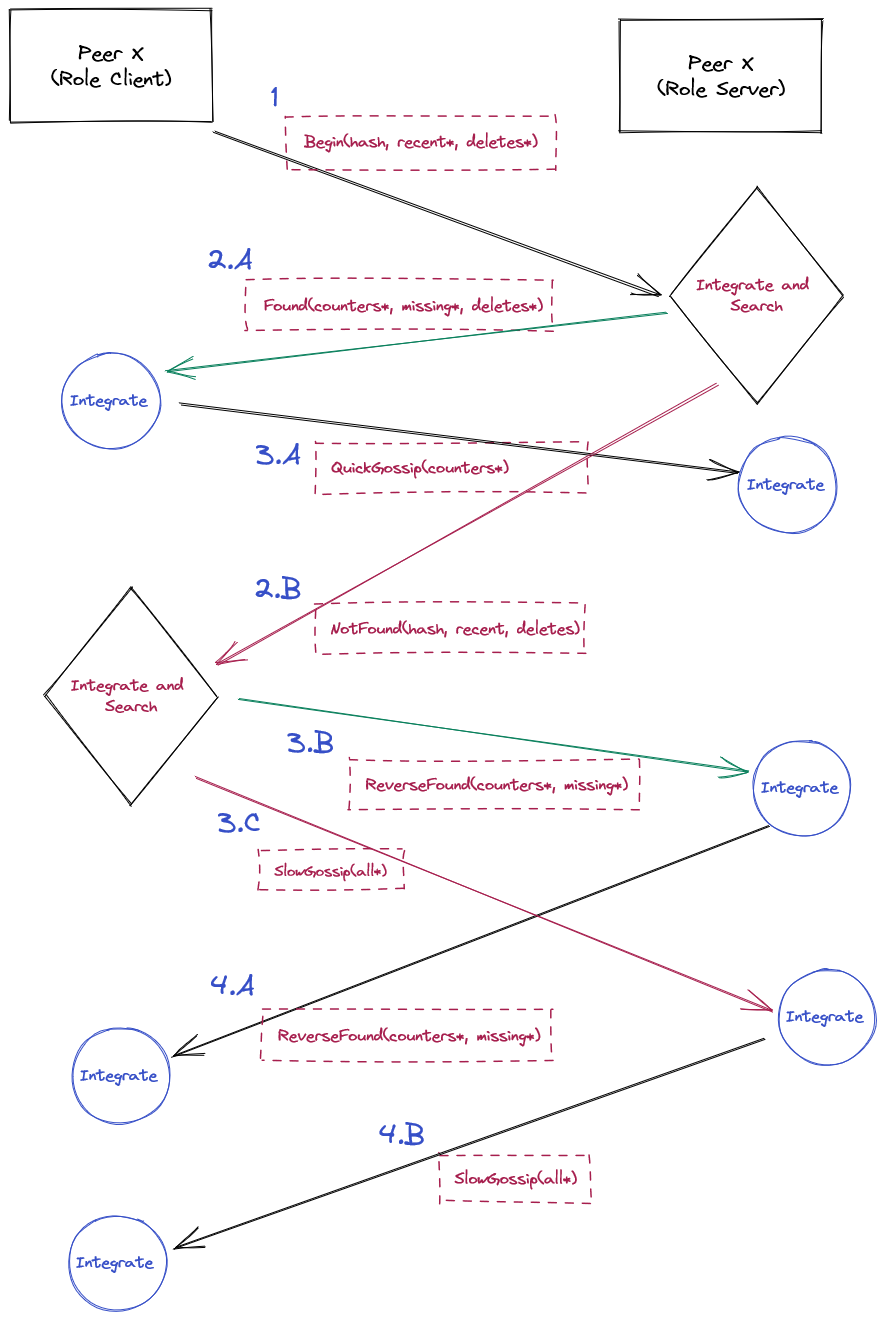

In designing it and leveraging gRPC, I did invent an interesting way of gossiping using ideas slightly inspired by blockchain (or, at least my poor understanding of blockchain). Let’s check out the diagram, and then I’ll explain how it works:

Step -1: Understanding how gossip failure detectors work at core

The key idea is a server will heartbeat itself at a regular and predictable interval (every second), and this heartbeat is put into a mapping of server id to counter. This map is then gossiped (i.e replicated) around the network, and any peer can detect failure of server X if the counter for server X hasn’t changed in some time.

For example, if I know that a server heartbeats every second, and I haven’t seen that server counter move in 10 seconds, then that means it is probably dead. The PDF touches on the math, but the neat idea is that counter spread is exponential. If you have 1000 hosts, then most recent counters should spread to every host in 10 to 11 seconds. The 10-second time for 1000 servers to detect failure is a maximum time as you are gossiping updated counters every second as well.

In the way that I’ve implemented, there are only a special finite set of bootstrapping hosts that are special. They are special in that they should always be available to bring others into the set of machines aware of each other. Beyond that, peers are equal in terms of their role. They wake up periodically (i.e. every half second), pick a random peer, and then begin an exchange (See step 1). Now, it’s entirely possible that peers pick each other which we will ignore. This exchange leverages the above flow such that both peers at the end of the exchange have shared the counter per server id being tracked.

Step 0: Let’s understand the data model

Gossip manages a set of instances where each instance is the tuple (id, endpoint, role, counter). An example instance is (“12342-242-423242-1221”, “10.10.10.24:2131”, “adama”, 542). We put a bunch of these in a set, and call that set an instance set. This set is then use to answer queries like “get all active instances of role ‘proxy’”. If we treat an instance set as immutable, then we ask how can the instances grow and shrink as capacity changes? This is where the instance set chain comes into play.

The instance set chain is a map of hashes to instance sets where the instance sets share access to instances by reference. The map holds onto a finite number of items (using MRU cache rules) and for a finite time. The key idea at play is that capacity changes are not frequent, so we bias towards a quick gossip being the ideal where only counters need to exchange.

Ultimately, gossip requires peers to exchange counters since the counters provide failure detection (see step -1). The key challenge of exchanging counters is having a common ground for peers to exchange state with an implicit mapping. The hidden requirement here is that we want to optimize away from exchanging everything which is wasteful due to sending duplicate information. The hash establishes a quick way for two peers to exchange the valuable mutable content (i.e. the counters) without exchanging the unchanging immutable contents (id, endpoint, role).

The chain is then the implicit history of the capacity changes such that peers can efficiently gossip on previous capacity and then focus on reconciling recent changes directly.

Step 1: a client emerges and picks a random server peer

The initiating peer (i.e. code using the client) will send the remote peer (i.e. code responding via a server) a few things:

- the hash of the set of instances it is using

- a list of recent instances that it learned about

- a list of recent deletes that is has either performed or learned about

Step 2.a and 2.b

The remote peer will integrate the recent instances and deletions from the initiation. It will then look up if it has the incoming hash within its history. Either it will find the hash or not.

If it does, then step 2.a is taken where it will tell the client that it found the hash, provide a listing of any instances it thinks the client is missing, and provide a listing of recent deletes it has performed. This is the happy case leading to step 3.a.

If it does not, then step 2.b turns the tables around. This means telling the initiating peers its hash, its recent instances learned about, and a list of deletes it has performed. This step 2.b is essentially a reversed initiation which leads to steps 3.b and 3.c.

Step 3.a: complement the exchange

Both the peers have a shared basis for communication, so the initiating peer absorbs the counters from the remote peer then sends its counters. This is the optimistic happy path, and with three messages the counters are exchanged.

Step 3.b and 3.c: the reverse side

The remote peer turned the tables, and the initiating peer will now integrate the recent instances, recent deletes, and then look for the hash. Either the hash is found, or it isn’t.

If the hash is found, then the client will send its counters along with any missing instances to the remote peer as step 3.b. This leads to step 4.a

If the hash is not found, then the client and server have no basis for efficient communication and the client will send all instances to the remote peer via a slow gossip as step 3.c. This leads to step 4.b.

Step 4.a:

Both the peers have a shared basis for communication, so the remote peer absorbs the counters from the initiating peer. It then responds with its counters completing the exchange.

Step 4.b: slow begets slow

The forceful sending of everything catches the remote peer up to date, so the remote peer then responds with everything as well. This completes the exchange at a high cost. Ideally, this is the thing to monitor as it is expensive. However, we keep it to a minimum by using the recent learnings and deletes to quickly catch up changes. New capacity is also gated by the bootstrap hosts which will have the most accurate learnings of new instances, and this has the impact of anchoring the chaos introduced by new capacity.

What about deletes.

Removal of failed capacity is a tricky business especially with clock drift. Since deletes cause churn, we want to be careful with how we think about them. Currently, instances are considered dead if they haven’t been heard from in 25 seconds. An instance is eligible for deletion if a peer hasn’t heard from it in 20 seconds. This gap accounts for 5 second clock drift, but ensures that deletions run quickly throughout the system. I intend to play with these values as I tune the system since this time impacts availability and latency SLA.