March 14th, 2021 A manifesto of user interface architectures By Jeffrey M. Barber

The chat demo scripts work with an implicit mental model using the browser, and this post aims to take that model out of my head and make it explicit. For lack of better words, this has turned into a manifesto for user interface.

The model

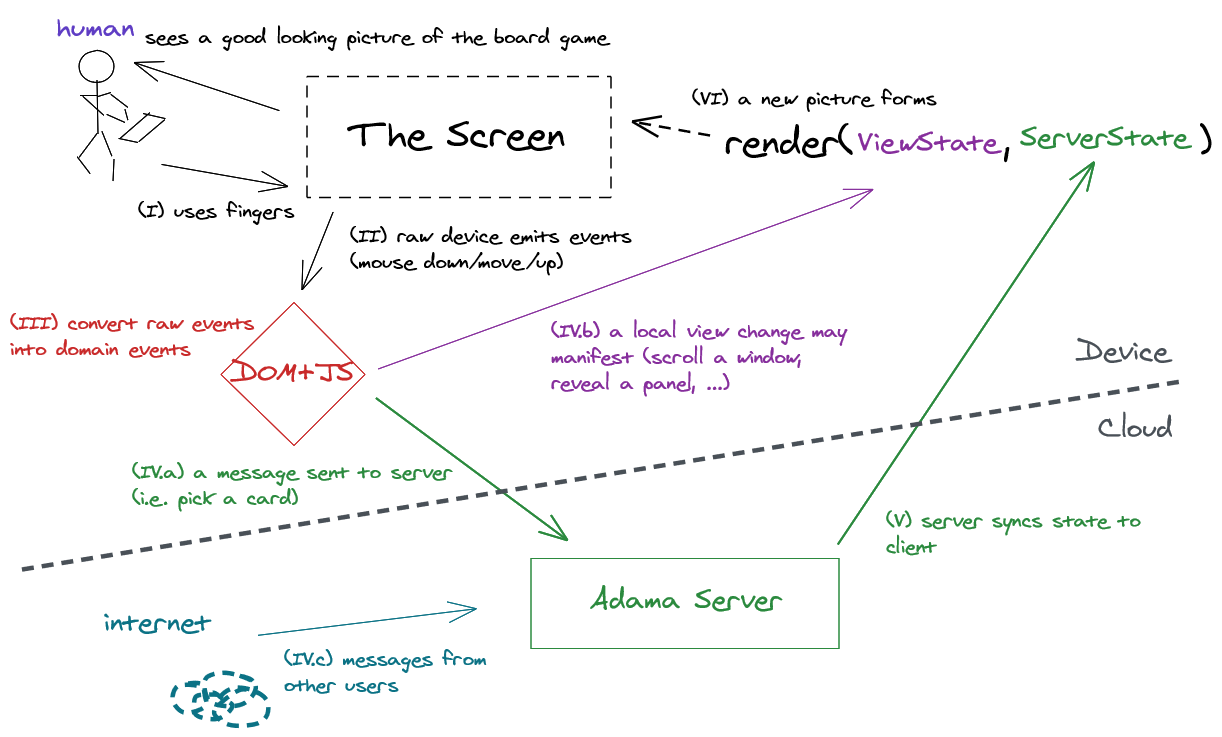

The below picture illustrates the picture for the mental model of what I’m thinking to simplify the architecture for the board game user interface stuff.

The mental model starts with you, the human user. You are alone in front of your computer playing a board game with friends online, and you see a nice image on the screen. You move your mouse or position your fingers and you interact with the picture (I). This device interaction leverages low level signals of mouse/touch down, move, and up (II).

The current system is the browser using the DOM and some JavaScript to convert those raw signals into something more useful (III). Either the signals manifest in a message being sent to the Adama server (IV.a) or update some internal state within the browser (IV.b: scrolling around or opening a combo box).

While the user is sending signals to the Adama server other users are also sending signals to the same server (IV.c). The Adama server synchronizes its state to the client (V). The DOM combines the hidden viewer state with the server state to produce the pretty picture (VI), and this establishes the feedback loop between many people playing a board game using Adama.

It is ruthlessly simple, and we can discuss a great deal of interesting details. Join me as I wander around those details.

Limits of the network

The boundary from client to server may be vast on this blue marble we call home. Unfortunately, the network is not perfect, and you can expect delays disconnects when things go bump in the night. Things will go wrong, and products must tolerate it in a predictably reliable way.

We can talk about a couple of models that work well enough.

First, perhaps the state is so small that you can just send the entire state in both directions. This is great as this model can tolerate packet loss, and you can simply use UDP and just add a sequencer to your state such that you ignore old state. The key problem with this model is that it isn’t a unified solution; product growth and complexity will eventually force you away from this model such that you either you abandon it or complement with a tcp-like stream.

Second, once you have a tcp-like stream then you have the potential for an unbound queue. Some products and games can absorb this overhead because games end, so their bound is implicit. Heroes of the Storm and Overwatch do this as they capture replay logs and joining a game has a non-trivial download. This feature implies usage of the command pattern such that all state changes are guarded by a queue of commands, and if you can serialize the queue then you get both replay and network synchronization features.

public interface Command {

void execute(YourGameState);

String toJSON();

}

This pattern provides an exceptionally reliable framework for keeping products up to date, but you must be willing to pay the high cost during failure modes. Perhaps, the protocol can help such that only missed updates are exchanged; however, the queue is still unbound. Fortunately, cloud storage is so cheap that every command humanity could ever emit could be persisted forever. Sadly, clients lack the bandwidth to reconstruct the universe, so this is not the unified solution. Furthermore, the serialization depends on the implementation of the Command; it is a common problem between versions of games that offer replay to wipe out existing replays due to versioning issues.

Another nice property of the command pattern is that you can leverage client-side prediction such that you can run your client’s state forward while the network delay and server unify input from all people. You can detect conflicts between the client and server, roll back state, accept the server’s commands and then replay actions locally. This will cause a temporary disturbance, but the state will be correct without divergence. Now, board games do not require client-side prediction, but it is something to keep in mind.

The unbound queue is a problem that I am interested in especially after a decade dealing with them in infrastructure events. The solution is to bound the queue. There are many ways to do this. For instance, you can just throw items in the queue away; this is not perfect, but it is a common and good way when the contract for customers is to retry with exponential back-off. An alternative way is to leverage flow control such that each side has a limit of what it can have in-flight.

For the messages sent from client to server, flow control is perfect such that the client is only able to send some number of messages or bytes without the server acknowledging its commitment. Problematically, flow control breaks down from server to client for two reasons. First, there is more data flowing from server to client as it is aggregating data changes from everyone. Second, the pipe can get clogged as the command pattern requires a potentially infinite stream of updates; it is easily possible to never catch up especially if the client is on bad network or has a slow CPU.

This is where my math-addled brain realizes that this is solvable with algebraic concepts. Instead of the command pattern, we can use state synchronization with state differentials. For board games (and games in general), the state is bound (there are only so many game pieces within the box). With a finite state, you have a maximum transmission rate of the just sending the entire state as fast as you can using flow control to decide when to snapshot the state. This upper limit means that blips in the network just manifest as strange jitter.

This requires a data model that supports both differentiation and integration, so now you know why you studied Calculus as it is universally applicable. This is why Adama is using JSON without arrays along with JSON merge as the algebraic operator; arrays are problematic, and they can be overcome with specialized objects. This means that an infinite stream of updates can collapse into a finite update. This allows flow control from server to client be effective and cheap.

Alas, this amazing property is not without cost. This capability makes it hard for people to reason about what happened as there is no convenient log anymore to tell them directly. If players care about understanding what happened because their focus drifted, then you lose the ability to have nice change logs like “player X played card Y, and player Z discarded two cards”. Instead, you must construct these human friendly logs on the fly by describing the change from just the before and after states. There are no silver bullets in this life…

Now, is this important for board games? Yes and no. It mirrors the problems of using a video channel, and if there is a disruption then people can just ask “Hey, what just happened?”. The technical problem is easily handled by kind humans. However, there is exceptional value in solving this problem.

How Adama addresses this network business.

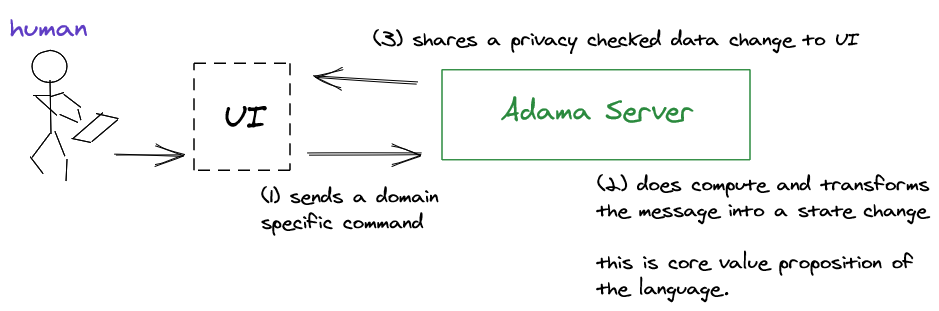

Clients send the Adama server a domain message which has the spirit of the command pattern. For instance, the message could be “pick a card” or “say hello”. The key is that the message is a command the client and human care about within the product’s domain.

The Adama server will then ingest a domain message and convert it to a data change deterministically. Not only will this happen for the current user, but the Adama server brings together many users. Adama will then emit a stream of data changes to the client which it can leverage to show the state.

The key is that the language bridges the complexity of thinking about data changes by enabling developers to think imperatively within the domain exclusively. As the language emits state changes, the platform can broker those state changes to the client using flow control. While the client is not ready to get an update, the platform can batch together changes using the algebra of JSON merge. This will ensure that clients with adverse network conditions will snap to the correct state without overcommitting to an infinite stream of updates. This model also works well with catastrophic network events like a loss of connection as the client can just reconnect and download the entire state at any moment.

All of the complexity and pain of using the network goes away if developers commit to holding their hands behind their back and watching the JSON document update.

Rendering combined with state changes

With efficient network synchronization figured out, the next step is to figure out how to make a nice picture.

The chat demo uses the DOM such that state changes from the server are converted directly to DOM changes, and this works well enough. There are some gotchas. For instance, the DOM has a great deal of view state which is not convenient to reason about. An example is using innerHTML to do updates; this can be destructive to internal state like scroll bar position or text input entry.

However, we can outline the nature and shape of all state changes. As a prerequisite we must establish that the state has a static type so we should not expect strings to become objects and vice versa. With this, we can see state changes manifest as:

- values within objects changing

- objects having fields update

- arrays having elements removed or added

- the order of elements within an array changing

Given the simplicity of json, there are few possibilities when the types are consistent between updates. If types can change, then bad times are ahead as the complexity blows up!

Fortunately, with JSON being a tree and the DOM being a tree means synchronization is straightforward while there is one to one correspondence. When you start aggregating the state into the DOM, then things become more complex. However, you could offload that aggregation to the server via formulas. If the DOM representation looks like a mustache template over a giant JSON object, then good times are ahead.

Enter the canvas

Alas, the DOM has limits for some of the scenarios that I was envisioning for another game where I started to get into the land of canvas. Canvas is the 2D escape hatch such that all your fantasies come alive… at great cost.

Now, I love writing code using the canvas. It takes me back to mode 0x13h days! Naively, it’s straightforward to write a render function that converts the state into a pretty picture. However, a predictable game emerges.

First, you will want to convert raw mouse/touch events into meaningful messages. This manifests in building or buying yet another UI kit. Fortunately, for simple things this is not a huge problem and it is easy to get started. However, this is the seed to any UI empire, and it’s generally better to buy a UI framework than invent yet another one.

Second, you give up on accessibility flat-out. Is this OK? Well, this is the normal and sad state of affairs for most games. However, I feel like we can do better. The key to accessibility may rest in thinking differently for different handicaps. For instance, if I can solve how to make games playable via a home assistant like Alexa, then I can bring the blind into the game. If I can simplify the user interaction to rely on a joystick and a button, then mouse precision can be factored out.

Third, there is a performance cost for rendering the entire scene based on any data change. Given today’s hardware this is abated by hardware acceleration and generally is fine. However, this is a white whale as it would be nice to scope rendering updates to where data changes manifest visual changes. This requires building a renderer that can cache images between updates and then appropriately invalidate them on change, clipping rendering to a portion of the screen, not drawing things that don’t intersect the rendering box, and other techniques.

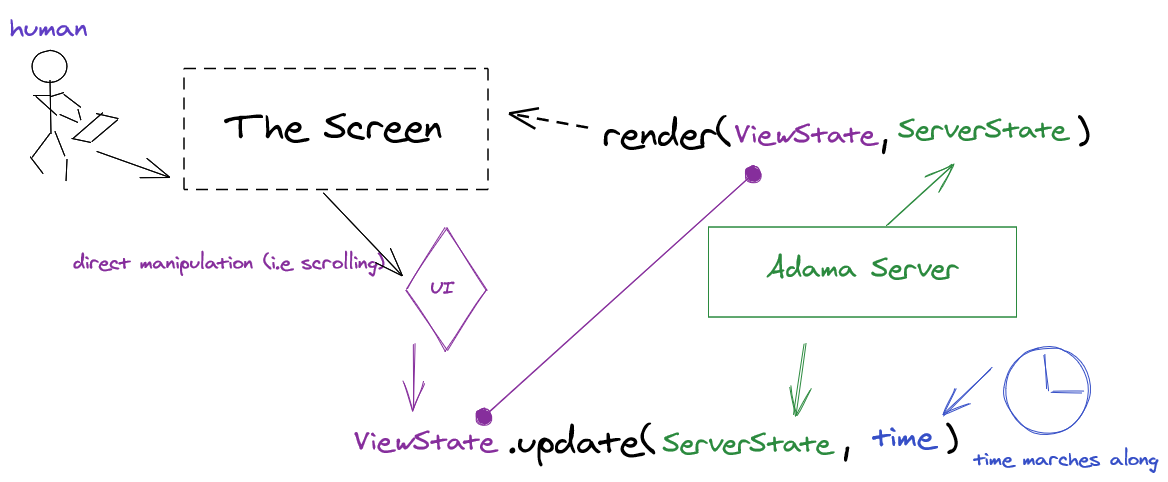

Fourth, you may interact with the picture by scrolling or selecting a portion of the data to view, and this gives birth to view state. While this is not a huge problem, it requires being mindful of where the view state is stored. I believe the view state should be public, and this has the nice feature of having deterministic rendering. If local changes are extracted away, then the render function can be a pure function with both view state and the server state as inputs. This gives rise to the capability of unit testing entire products with automation! It turns out that private state within objects makes life hard, and object orientated programming was a giant mistake.

Fifth, rendering the JSON scene will lack smoothness. The picture will just snap to state instantly, and while this is great for testing and predictability. Humans need animation to visualize change. This introduces the need for view state to smooth out the data changes, and this requires an update step to transform the view state based on server state and time.

Time must exist outside the update function because this forces the update function to be deterministic in how it updates the view state. Determinism is an important quality, so this also means not leveraging randomness. This vital property enables testability of products.

Regardless of the bold testability claims, the key is that the shape of the solution for all of these issues start to evolve the DOM. The hard lesson in life is that you can’t really escape the DOM. You can call it a rendering tree, scene tree, or scene graph; however, that’s just different shades of lipstick on the pig.

Future Thoughts

Like a fool, I’m thinking at this deep level because I am toying around with the idea of building yet another cross platform UX ecosystem… for board games… in rust (and web). The core reason is that I really-really-really hate other UI frameworks and development models. It’s worth noting that I built a similar UI ecosystem a decade ago, so this isn’t my first rodeo. The target back then was the web with crazy ajax, but my failure back then was a lack of accounting for SEO which was a death blow back then; in today’s landscape of PWAs and SPAs…

Developer tools is a murky business, so ultimately this is not a business play (yet?). It is a mini empire play with a niche focus, and I realize this requires ruthless focus. However, the siren song and distraction is cross platform lust.

First, I want the web because the web means online.

Second, I want mobile devices, and the web works here as well. However, I would prefer a native app because I’m a performance junkie.

Third, I want it to run on Nintendo Switch because I like the Switch; it is a fun mobile platform. I still need to get the indie dev kit and check out the licensing. If the switch works, then all consoles should work.

Fourth, I want it to run on TVs which are basically either mobile devices or web, so I should have my bases covered. The only caveat is that it makes sense for TV to be a pure observer, so people can congregate in the living room around the big screen.

Finally, as a fun twist, I want home assistants. I want to be able to play while I cook or while I exercise.

All these wants can be so distracting, so the hard question is how to focus. The platform specific user interaction idioms are a nice way to tie my hands behind my back as I slam my head into the wall of building yet another framework, and the key is to keep things simple. As an example, I will need to have a library of solid components. The tactical mistake is to go forth and focus on all the low hanging components like label or button. Rather, I should focus on a meaty domain specific component like “hand of cards” as that would be used in card games and deck builders. The effort then is less empire building and focused on solving a rich domain problem, and the design game that I need to play starts to take shape; this component design game has some rules.

First, the component model assumes the component will fit all activities within a box. This feels like a reasonable boundary.

Second, the input language for the control is limited and there are five forms:

- tap(x, y)

- move(left, up, right, down)

- main button

- accelerator button(…)

- voice intent

There are interesting challenges for both d-pad movement and voice intent, and this will require an interesting design language to sort out.

Third, the component must describe or narrate the state change effectively. For instance, a “hand of cards” component would describe detecting a new card appearing as “a two of spades was drawn” while detecting the loss of a card would be describe via “the ace of hearts was discarded”. Now, this narrator business is an exceptionally fun challenge because language is interesting to generate. Not only does this provide a change log history, but it also enables home assistants to narrate the game.

The mission of the UX ecosystem is therefore to unify all these idioms into one coherent offering such that board games are easy to interact with regardless of the platform. Is this a silly endeavor? Perhaps…